Quick access

- Contextualising insights

- Sharing

- Being part of a community

- Ethical responsibility and missing debates in service design

- Who gets to design?

- Diversity in the discipline

- Accessibility, communities, and emotional impact

- Practitioners also found problematic how we engage with communities

- Missing debates about the emotional impact of engaging in service design

- Power, bias, and the need for reflection

- Shared principles for inclusive design

Contextualising insights

These insights come from 15 remote interviews.

Although we speak of service design practice, we use the term service design very broadly.

- half of our interviewees self-identified as service designers or have service designer as their job title

- We interviewed people working in different locations across Scotland

- Some practitioners worked as free-lancers, consultants and contractors; others were employed by design agencies; and others were employed by public and third sector organisations

- All interviewees had a mid to senior level of experience working either in service design or in public/third sector

When we refer to ‘practitioners’, we refer to people who engage in service design approaches and practice within the Scottish public and third sectors independently of their job title.

Sharing

Networking — keeping in touch

Most practitioners attend various Meet ups, join Slack groups, mailing lists, keep in touch with previous colleagues and follow others on Twitter.

On Twitter, some observe more than interact. It’s a place to filter information.

“[I] follow people to keep an eye on what is happening in the community”

“Thanks to the algorithms, I get a sense of being able to keep up with people I’m really interested in”

But watching your networks to filter and select the events worth attending is still energy and time consuming:

“I need to gather the energy to figure out [what event] is most beneficial for me to attend”.

Service design is a field that forces you to have a wide set of skills and learn from a lot of sources, but there is a lot going on and it’s not always easy to keep up.

A lot of events, but not inclusive enough

Because of COVID, events are now online which creates new opportunities but also place barriers and exclude some people:

“As someone with a disability, this sort of communication [via Zoom] is so exhausting”. […] I feel extremely excluded from the service design community. I have enough of a problem working on a day-to-day basis […] just creating a space for me to exist as myself. So keeping in touch with the rest of the community is impossible.”

How and what do practitioners share

Practitioners share case studies, what they are learning or reading, what they are working on or experimenting with. But some felt that we should share more: we “don’t even share the good stories”.

Many told us they share with others via blog posts and social media, speaking at events, via or sharing with colleagues within their organisation.

Some prefer sharing informally within communities of practice:

“There are some positive communities like on Slack, like the SDS [Service Design Scotland] as a way to connect with people, […] these things are more informal, kind of go along, everybody has a chance to chat, meet people, and that’s quite different from going to a talk, a workshop or a conference where you go to keep and absorb as opposed to share?”

There a lot of reasons why people do not share

Sharing takes time

For one practitioner, knowledge sharing was part of their delivery cycle. But more often, people who wanted to share their work did not always find the time, so they may share in more informal ways.

Client anonymity

Some can’t share because of an NDA (Non Disclosure Agreement)

“I do a lot less public sharing of things. It’s because of a mix of things, it’s harder to share clients stuff, especially now as I can’t share anything about my current project, [..] you’re limited by that, so it’s time but also the effort for getting out what you can say.”

Some were afraid to share the ‘negative’ as people might stop trusting the process

Service design “is something quite new and we are trying to get people engaged in it. [So] it is right to be cautious about how we talk about it. […] there’s a risk in it and you have got to trust the process.”

Some felt they didn’t have something worth sharing

There were many reasons for this:

- So much out there already

- Lack of confidence “it feels very difficult to share learning because we are not very confident in what we are doing”

- Feel we can’t share when something failed

One practitioner thinks that “people who end up working in the public sector are really good service designers and are also ambitious. They want to show the good work that they’ve been doing.” But doing so, it felt that our interviewee could never reach that level and they “felt down on themselves”.

Another expressed a similar feeling:

“It’s hard, because every time you speak to other service designers, or you look at the Scottish Government community or SAtSD (Scottish Approach to Service Design), you feel a bit like you are doing it wrong, or you feel embarrassed of your own practice”

A Lack of space for honesty

Many practitioners felt we needed more honesty when things went wrong and share about failures, not just celebrate successes.

“You would never see that from the person on the stage saying “oh boy that was bad, and I totally messed up”

“We should not be scared of sharing how the process looked and what the failures were.”

Some felt people were “playing safe” a lot, but maybe it was because they were in “survival mode”: they might be out of work or have too much work?

The Service Design Network organised a Meet-up on failure in Glasgow on 24 July 2018. There was a huge turn up and ironically, a lot of things failed during the event: the sound was poor, it was really hot in the room and more. At least three interviewees mentioned that event because it was one of the very few occasions where failure was discussed.

“I felt it was therapeutic for service designers. Because actually I could hear that a lot of the issues that we have in our organisation are shared by others”

This was a feeling shared by the practitioners who attended our workshop on design contributions and barriers:

From the feedback frame of the workshop on Miro

Being open, sharing resources and research

In the third sector, “we’re doing things that connect charities very well, having webinars, briefings, WhatsApp groups… But it doesn’t go deep enough. You’re not sharing resources, you’re not working on the same projects, you’re just kind of tuning into what other people are doing”.

Some practitioners would like “some kind of open source way of working where you actually open up what worked well on a project. In the public and not-for-profit sectors, it should not be an issue to open up all the documentation on how you have tackled a particular issue in a particular community and how this service is now up and running and how it was co-produced by various different partners working together”.

Some went further, thinking sharing should not only be within the Third sector, or even with the Public sector, but felt that we should include the private sector too: “I’d like there to be a bit more focus on what we have in common”.

“We all face similar challenges, so we need to support each other a lot better.”

“The biggest challenge we’ve got is doing the same thing again and again re-inventing the wheel, we’re conducting the same research again, looking at designing the same patterns again, not reusing design patterns from different spaces and not considering design patterns in different ways and how they might be applicable in different sectors or spaces”

If we don’t share, “what we will end up with is everybody, everywhere, every local authority goes off and design services, every GP and NHS services goes off and design some appointments and booking systems”.

Community as a place to share

The next summary will be about being part of a community.

We want to keep these summaries short, so we extracted the sharing theme from the community one but they are strongly linked to each other: many practitioners described an ideal community as “a space where people feel safe to share and are nurtured by their peers”.

Being part of a community

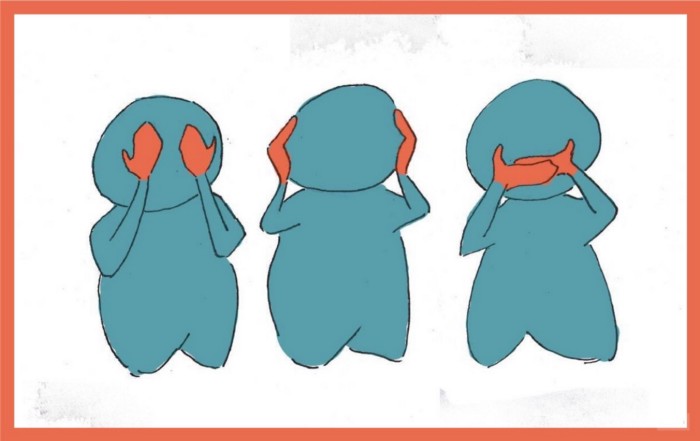

Illustrations of this part were made by Angela and Stéphanie

We asked practitioners how they build collaborations with other people practicing in their area, and where they thought the Service Design community in Scotland should concentrate its efforts. Interviewees told us about the communities they participate in, and the communities they would like to have.

“Community” was used broadly and meant different things at different times for our interviewees. It could be the Scottish Service design community, but also a wider Design community beyond Scotland (and even beyond the UK), and sometimes, it meant the community they live in.

We saw that some of our participants didn’t feel safe to share. But quite a few also told us that they felt “outside” the service design community despite their experience. We spoke about the lack of honesty and critique in online spaces, and the benefits that practitioners gained from sharing in more private spaces. In this article we expand on these issues.

These insights can help us build better communities.

- What practitioners like and dislike from the communities they belong too

- Tips on how to set-up, grow, and manage communities of practice

Feeling like an outsider

Even though all of our interviewees had a mid to senior level of experience working in service design in public and third sectors, many still felt like outsiders:

“Our community is not inclusive at all. It’s so difficult, and I feel often that I am on the outskirts of things. Which makes it really difficult to articulate your place.”

An expectation that you have to put yourself forward

In our previous article we saw that people do not feel confident enough to share or feel inadequate because of the amount and quality of work shared by peers. Similarly, some people feel excluded from online design communities on platforms like Twitter because there are“a lot of really loud voices”. Practitioners feel pressure to share their work “because we’ve created this space where we constantly have to put ourselves forward”. But this “is not for everyone”, and people feel they cannot share at the pace that “big names in the field [do:] constantly networking and talking about the things that they are doing…”

Some cliques, design rhetoric and lack of critique

Another way in which practitioners felt as outsiders in design communities was connected to the lack of honesty in the ways we share our work in public forum. A fair number of practitioners criticised the general design discourse and uncritical praise.

Some groups are seen as “people [who] just go and praise each other about the work they are doing without thinking critically about it”.

“There are some people in the community that are put on pedestals without interrogating them at all, it’s just about visibility, who gets to be seen, who’s story gets to be told.” [‘Community’ was meant here as Design community and not just in Scotland] Some people feel disengaged because they are frustrated by “the rhetoric, conversations, and behaviours in some service design communities”. In a future article we will speak about the debates that practitioners feel are missing in service design communities and discourse.

What do we want this community to be?

From our interviews, it became clear that communities of different types and sizes offer different kinds of value to practitioners. They find value in spaces with different degrees of privacy and management, as well as disciplinary and geographical outreach.

A space where people feel “safe to share and are nurtured” by their peers

Public spaces to display our work

Some practitioners felt that we still needed to join efforts to better present our work, “show what service design looks like: […] real delivery in really complex and difficult environments”

Closed groups

Some designers are more comfortable having a closed group of people for deeper conversations, either within their organisation or through personal networks, with designers or across multi-disciplinary communities.

Designers only

As we saw in our previous article, practitioners benefited spaces where they can honestly share the challenges and experiences of their work. Conversations among designers are also important for “moral support”.

Personal networks

Some people who don’t “feel very welcomed in set design communities […] shape their own communities” through personal connections. These personal communities allow for more “emotional conversations” and, since lockdown, some groups have strengthened these networks by meeting weekly with colleagues inside and outside design.

Spaces for collaboration

We also saw that the community yearned for wider, collaborative spaces to share resources: spaces “to be able to facilitate and reuse elements and exchange knowledge”.

Who should be part of this community?

Some think that design communities are “very disparate and siloed, [leading to a] loss of knowledge and sharing”. People spoke about a lack of sharing across communities and the creation of “walled gardens within the international community of service design — people try to build walls around [their communities and work, as a way] to make money to survive”. But our “ethos moving forward” should be to “create free and open connections between people”.

Some people value informal networks, “environments where people come, find each other and start to flourish and develop naturally as a network of people”. You could “collaboratively share things, in an informal way”, that’s “how people learn”.

Communities beyond design

While there is value in designers’ only spaces, a few practitioners valued cross-disciplinary communities and wanted to engage with a wider community that encompasses overlapping approaches.

Some felt that, in existing communities, “you have public and third sector people of a particular level. You don’t have the people on the whole delivering the services in that space talking about it. You have managers or strategic level people”.

There is an interest in sharing learning with other “disciplines that work in similar ways”. Having “ other perspectives [will help us] see the bigger picture here, [so] why don’t we just have a community of people who are contributing to change, based on people’s needs”.

How big do we go? The whole of Scotland? Wider?

Local networks

Practitioners valued local spaces because these help them build connections with people close to work in similar spaces across organisations, sectors, and fields of expertise.

Scotland-wide community

Some interviewees saw value in service design practitioners coming together as a community to defend our collective interests and improve our practice. For instance, an interviewee would like to see a collective response to briefs and tenders that do not line up with service design approaches. Another participant noted that other design fields; such as architecture or landscape design; were seen as “much more mature in terms of profession [and thus benefit from] clearer ideas and opportunities”.

Another interviewee noted that “a lot of the public sector designers [in Scotland] are not on a high enough level to be able to change things within their organisations or in the national” landscape, but “there is a strength in numbers [and] as a group you‘re much stronger to be able to do that or to get there collectively.” It just helps people to get case studies, get joined-working, have a platform to shout louder about it”.

International exchange

Some were looking for global exchange of thoughts, ideas and generating dialogues between the Scottish and the international community.

“GDS (Government Digital Service), they are just neighbours. They speak in the same language and they work in a similar system. But it could be other nations, other places. I think we should expand our view a little bit. It would absolutely need to be adapted, but we can at least look at it.”

Building strong communities of practice

Practitioners also offered some tips for building a good community of practice.

First, it needs a catalyst

“It needs to be started by something or someone”.

Like for the Service Design Scotland meet up group, started by Mike Press and Hazel White from Open Change, which became the Gathering (#SDSGather) during Covid with Barbara Mertlova and Lorri Smyth who help running them. You can join the associated Slack Space even if you are not in Scotland

It also needs someone keeping the community alive

“Watching and listening, keeping the energy and people un-bored, making sure people are connecting”. But it should be simple to keep it “vibrant and informed, helping people get value” from it.

It is most beneficial to the community if there is someone who “has an oversight of what is happening across the community to help connect people”.

The value of small communities of practice is difficult to scale up

They allow practitioners to “collaborate [using remote tools]. But if you scale that up to a Scotland-wide prototype, it becomes a very messy Miro board or team”.

Sharing resources needs data management

Pondering what kinds of things could be centralised, an interviewee pointed out that communities of practice often develop “quite organically” which offers lots of interesting things. But sharing resources requires more work behind the scenes.

Some suggested looking at the user-centred design communities in government (blog post of reflections about it by Kara Kane and Clara Greo) or the ResearchOps community.

“It’s a group of people who take responsibility for doing certain things, it’s owned by everybody but nobody.”

“That community is huge and … what is inherent to that community is that kind of librarianship, some people who will really keep information managed really well… They listen to the community, they know the sentiment, what’s coming up, respond to concerns that they see emerging, and the amount of information that people are sharing about their own work, about tools and techniques is just invaluable.”

That’s been created because the culture of the space feels good to people. And it gives them value and they help run it.”

Centralising community efforts in Scotland: Ownership

A controversial topic might be who should manage such a community of practice in Scotland, since we had very different perspectives among participants.

An interviewee felt that “you need a government body maintaining uploads”, and gave as an example the Scotland Council for Voluntary Organisation (SCVO). However, “there is no overall body in the same way you would have an Architecture’s Guild” and it was difficult to envision a government body to cater for “everyone who is doing service design”.

Another participant thought the opposite, that “it would have to be of an organic community initiative” and should not come from a “particular sector or from government” as it “would immediately be boxed into that corner, where it‘s coming from. And that‘s the thing we need to avoid.”

We heard similar views regarding the Scottish Approach to Service Design (SAtSD) coming from the government as potentially being an issue. As well as felt that the SAtSD could fill that gap: “There is certainly disciplinary and cross-disciplinary stuff that could be going on if the SAtSD was an actual community of people.”

Ethical responsibility and missing debates in service design

Illustrations of this part were made by Angela

When we asked practitioners about gaps in service design practice, interviewees highlighted a myriad of issues; such as gaps in skills, lack of guidance and support, and gaps in design communication among others. In this article we focus on the ethics of doing design. Paraphrasing a participant, the complexities around bias, inequity, and social justice are important in any service design space but, especially, in the public and third sectors.

Even though service design prides itself in involving stakeholders and communities, nearly half of our interviewees felt that it still lacks inclusivity, diversity, and accessibility. They pointed out that debates around ethical responsibility, privilege, and power are largely missing in Service Design communities.

Who gets to design?

Participants questioned who should be designing services and who gets to become a designer.

A practitioner noted that diversity of backgrounds and lived experiences within the team are important because our differences bring something ‘magical’ to the way we approach problems. But the reality is that the lack of diversity in service design teams has left our individual and collective biases and privileges unchecked, which become manifest in the lack of inclusivity and accessibility of design processes and outputs.

Interviewees propose three strategies:

- opening up the discipline to more diverse people

- greater representation from users and communities within the design team

- greater self-reflection and criticality on behalf of designers

Diversity in the discipline

The lack of diversity in design teams was attributed to being ‘mostly privileged white people’ pursuing careers in service design, and the educational-hiring system being ‘a very privileged, very white pipeline of designers’. ‘Diversity in our teams will not improve until we stop expecting people to go through the same pipeline and come out as diverse as we need’.

Accessibility, communities, and emotional impact

Since our teams lack diversity, at the very least we should all ‘be doing more thinking around diverse needs’. We need ‘to understand the lived experiences of people with disabilities and health conditions and ensure that their needs are considered in your design process, even if you can’t get them into the room’. But many practitioners would like to see greater representation from users and communities within the design team, and are starting to question how to make the space more accessible.

Practitioners also found problematic how we engage with communities

We must ‘be critical about our own practice’ to become ‘inclusive in everything we do’, and build ‘stronger links to communities’.

Questioning the ethics of ‘being parachuted into projects to make something very quickly’

They struggle to create the time and space for engaging in discovery and establishing rapport with communities.

Missing discussions around the ethics of community engagement before starting a project

“Where you are going, who you are going to be with, how you are inviting people to participate, and whether they are given a fair value exchange for their time”.

Beginning to question and challenge the power structures embedded in designing services in the public and third sectors

An interviewee explained that, even though Scotland has the Community Empowerment Act, ownership of the outputs still resides with organisations. They felt that the ‘community should be the client’, otherwise ‘power corrupts the thing’. They want communities to gain more ownership and capacity to be able to take things further, and call out ‘a kind of design saviourism and a real lack of critical discussion and dialog among designers about things like power privilege’

Missing debates about the emotional impact of engaging in service design

Some practitioners felt we don’t talk enough about the emotional effort involved in bringing service design into a project, [the toll it has] on researchers, designers’, and how it impacts other communities that engage in the process. They were particularly concerned with bringing design approaches into public and third sector teams and organisations that lack readiness, and the impact this may be having on the people for whom design is a new way of working.

Power, bias, and the need for reflection

Some also call for greater self-reflection and criticality on behalf of designers to recognise our biases and how we create inequities by reinforcing power structures with our decisions and excluding people from our processes.

“We talk about designing for good, and there is [a] real optimistic positive energy around changing the world. That is really positive, but it needs to be grounded in reality. There’s a huge up-skilling need across the [service design] community to really think critically about the processes.” We need to understand how ‘the moral frameworks that we bring as individuals, teams, and organisations’ impact both our processes and outputs.

An interview pointed out that there is ‘a lot of talk about Design Thinking being the master’s tool, [but] it’s been really created by certain people for certain people’. As such, we must reflect about the processes, tools, and ideas that we use in our practice. We must understand where they come from, who created them, and who is being excluded. And we must find ways to make them more accessible and inclusive.

“What is it that we are hard coding by replicating some kind of practice for example? What are the inequities that we are creating and reinforcing in the things that we are designing because we haven’t thought about the origins of it or we haven’t thought about our own team bias?”

Shared principles for inclusive design

Our biases, assumptions, and use of language create barriers for inclusivity. But there is a lack of clarity or awareness of the principles and processes to work in an inclusive way. Practitioners call for a shared set of principles for inclusive design, and several pointed to the Design Justice Network: ‘a global network looking at social justice within design, and how designers can be aware of [how] the decisions that they are making reinforce power structures or inequity’.