Quick access

- Contextualising insights

- Service Design work

- Contributions

- Organisational barriers

- The Future of service design

- A service designer in every organisation

- Sitting in between systems and sectors

- Co-design as the default approach

- Collaboration across organisations

- Aspirations for third & public sectors

- Future of service design in Scotland

- Expectations from the future Service Design community

- An optimistic take on Covid-19

- Awareness and communication of service design

Contextualising insights

These insights come from 15 remote interviews and a two-hour online workshop with design practitioners.

Although we speak of service design practice, we use the term service design very broadly.

- half of our interviewees self-identified as service designers or have service designer as their job title

- We interviewed people working in different locations across Scotland

- Some practitioners worked as free-lancers, consultants and contractors; others were employed by design agencies; and others were employed by public and third sector organisations

- All interviewees had a mid to senior level of experience working either in service design or in public/third sector

When we refer to ‘practitioners’, we refer to people who engage in service design approaches and practice within the Scottish public and third sectors independently of their job title.

Service Design work

All illustrations for this part were made by Angela

What do practitioners do in public and third sector organisations in Scotland?

Although we did not ask interviewees directly what they did in their roles (see interview guide), a few activities stood out.

- Building design awareness & capacity

- Project and team strategy and direction

- Bringing an evidence-based approach

- Connecting things and people

- Improving services, processes, and systems

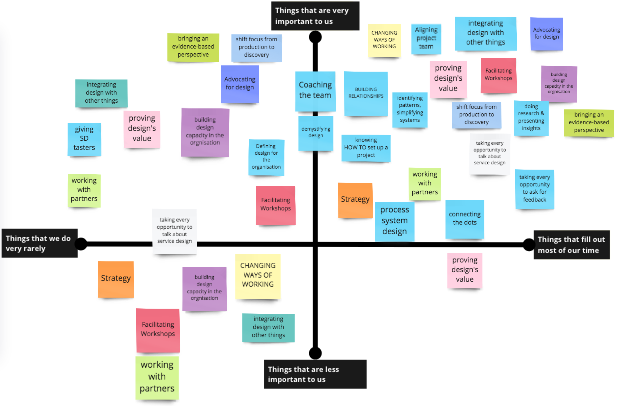

How much time practitioners invest in these or other activities will most definitely depend on their role. The workshop activity below shows that these activities have different weights in practitioners’ daily work.

Mapping activity part of the workshop we did — see the Google slides for it:

Beyond roles, interviewees also appreciated differences between working as an external consultant and working from inside the organisation that we would love to explore further. For instance, being an insider seems to allow a more holistic overview of how research and insights feed into the wider strategy.

Building design awareness and capacity

Service design practitioners in the public and third sector still constantly face the battle of advocating and proving service design and its value and on the other side demystifying, defining and clarifying it for an organisation or its people.

In many public and third sector spaces, design approaches are a new thing. So practitioners invest a fair amount of their time raising awareness, demonstrating its value, and building design capacity in organisations.

When design is not part of the organisational conversation, practitioners speak of taking every ‘opportunity to talk about service design’ and ‘bringing their service design skills’ to whatever role they are in and even when it is beyond what they ‘should do’.

But this lack of awareness means that they still feel the need to ‘demystify design’ and ‘push and prove’ its value for the organisation.

Once organisations are onboard, practitioners speak of defining the meaning of design for the organisation, giving design tasters, and building capacity.

They mentioned teaching user research, prototyping, the Double Diamond, doing service safaris, ideation…

One of the strategies mentioned was to send managers or key people at the top to service design training. But in order to make design available and be able to work with people in the organisation, practitioners need to ‘upskill and lift the bar across [the organisation]’. They need to reach a point where ‘everyone knows the language, why we are doing things, and why it is beneficial in the long run’.

Project and team strategy and direction

Service designer practitioners play an important role when setting up a new project or aligning projects including developing a shared vision, setting a strategy, and coaching the team.

Practitioners also drive project and team strategy. They have the ‘knowledge of how to scope out and set up a project in an inclusive and accessible way, how to research and analyse things, how to use different methods’… This allows them greater influence to encourage prototyping, make data and insights more open throughout the process, or feed ‘insights to be taken into account in various streams of work.

Furthermore, they facilitate and coach their teams. They make sure that they ‘get alignment within the project team’ to build a shared vision, and set up appropriate ways for the team to communicate.

They feel they coach, manage, and support their teams in a ‘refreshing, different way of thinking’. One that builds on ‘listening and learning’ and ‘empathy’.

Bringing an evidence-based approach

Some of the practitioners we interviewed were in ‘research heavy’ roles, and thus their work focused on doing user research, and presenting evidence back to colleagues and decision-makers inside and outside their organisations.

However, discovery is central to service design approaches, and practitioners in design roles however, when called into a new project, felt the need to shift the procurers’ perception of design from a ‘production task’ to a discovery process. While the initial brief may ask them to ‘design something that does this’, they come back with questions about ‘the problem’. They want to provide ‘a more impactful, long-lasting solution’, which requires ‘discovery, researching the problem, and involving people before you even touch the production side of it’.

Service design practitioners are heavily involved in research to ensure approach is based on evidence.

Public and third sector teams may have ‘never seen themselves as someone who provided a service’, even if they do ‘provide face to face and digital services’. They lack ‘the user experience perspective [and] the evidence that backs-up the existence of the service’ or their decisions. Instead, they have a back-to-front approach, where they know ‘what they do and why it’s good’

Connecting things and people

Practitioners also see as part of their roles ‘to connect the dots between different services, departments and organisations’; as well as integrating design approaches with other methodologies such as Scrum and Lean. They also found ‘relationship building’ important in their role, driven by their soft skills, openness, and willingness to share. The relationship building in the public sector is different due to the organisational structure, and the willingness to share as a (service) designer adds value to it.

There is this other side of relationship building, because it‘s quite important. [This public sector organisation] has such a different culture of leadership to any other organisation I‘ve ever been in or worked with. Relationship building and those skills from our sphere work, has been extremely useful like the openness, the willingness to share everything that we can.

Facilitation of people and workshops, internally and externally, was a key element of day to day work for many practitioners. They facilitate collaborations for the purposes of design research, collective activity, sense making…

Improving services, processes, and systems

Ultimately, service design methods seek to improve outputs, experiences, ways of working, services, processes, and systems.

Practitioners see huge potential for simplifying services and having systemic impact by improving everyday problems and interactions that occur across services. Efforts towards improving the system is possible by working within the system, which allows one to work more closely with users, staff, and stakeholders.

Practitioners also seek to influence and change some of the practices and ways of working in the public and third sectors to be more in alignment with service design approaches.

Some of this work is not as ‘sexy’ or tangible as practitioners would like. Integrating services may boil down to ‘creating an algorithm’, which success cannot be shown in images but in numbers.

A special thank you to Vinishree Verma, Carolina Moyano and Nicola Dobiecka for contributing to this work.

Contributions

Practitioners feel they primarily contribute by:

- fostering citizen/user participation and collaboration

- bringing in an empathic and evidence-based approach

- saving money through better services and practices

Interviewees emphasised three ways in which they make these contributions:

- bringing a service design perspective

- enabling collaborations

- engaging people creatively

All illustrations for this part were made by Angela

Bringing a service design perspective

- Getting findings heard:

Design research outputs; such as user journeys, blueprints, recommendations, or prototypes; contribute to ‘making change happen, and provoking conversations at senior management level’ - Building empathy:

Design has an emphasis on empathy and ‘being in someone else’s shoes’ to understand different experiences of services. Compared to other approaches such as lean, practitioners see service design as being more accessible, more customer-focused, and more exciting. Sometimes instead of contributing by bringing in the user perspective, the practitioner first needs to focus on getting buy-in to use these approaches. As an interviewee noted that, ‘some people [in the public and third sectors] think it is nonsense’ - Helping people recognise that they actually run services:

A participant emphasised the importance of ‘helping people recognise that they actually run services. ‘A lot of public bodies, receive money and annual policy letters and you have to turn them into stuff, but there is a whole lot of businesses with no one even thinking that they are designing a service’. ‘Seeing the world in a service way’ brings value to organisations by making those services tangible, so the people working there can ‘start to really see themselves as service providers’. It would be interesting to explore further how this shift in self-perception impacts the people running those services - Saving time and money:

‘Doing things the service design way saves time and money by making services more efficient’. The ’core purpose’ is to address ‘citizen needs’, while doing it in a way that ‘also benefits the [organisation] financially or in other ways’ - Building data-driven organisations:

Design’s evidence-based and iterative approach is about helping organisations to implement a ‘test and learn approach on an ongoing basis’ and ‘make decisions based on what you are learning’ through quantitative and qualitative data

Enabling Collaborations

Service design practitioners play an important role in enabling collaborations:

“Things don’t just happen in isolation [and,] often, the service designer is that link [or] focal point’ for different people and perspectives to ‘come together around essential points.”

Interviewees noted that public and third sector organisations have ‘to address complex, wicked problems’ where ‘working in partnership is key’, and having the ability to facilitate collaborations becomes essential. “

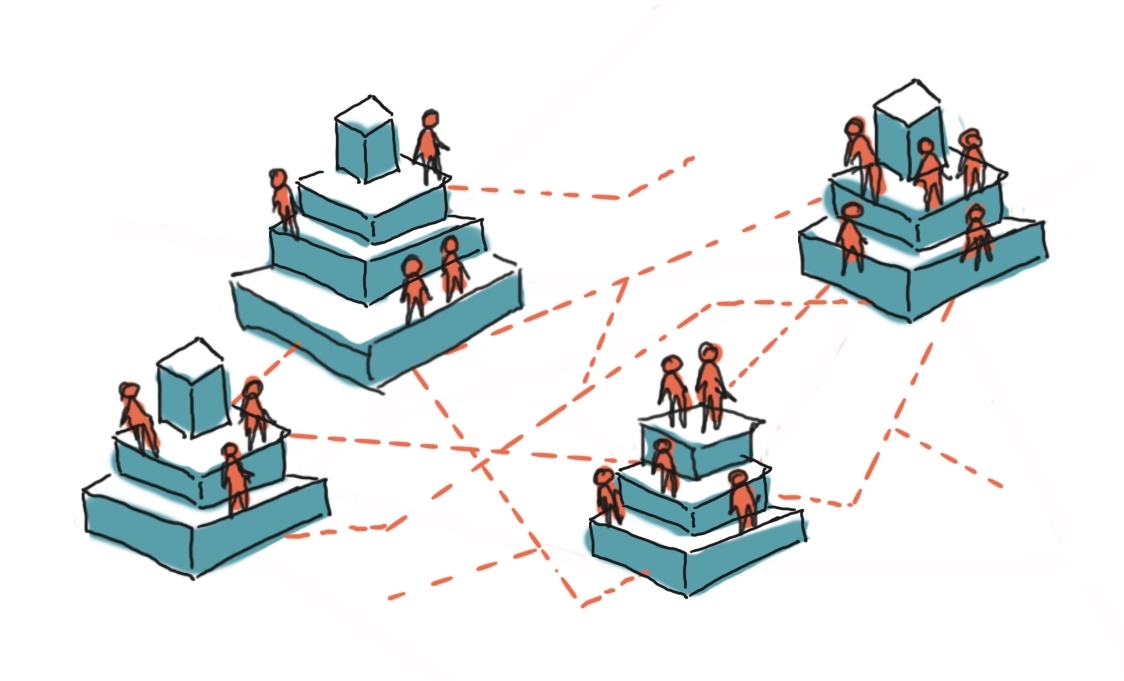

Service design practitioners have to become ‘the glue between the different partners and agencies’, design ‘what these relationships look like, and how [people] thrive and communicate with each other.” Service design approaches ‘give people an opportunity to stop and think’ and ‘creates the space to challenge’ how they currently work. But embedding these reflexive and collaborative practices in organisations in a sustainable way remains really difficult.

A key part of practitioners’ work is ‘to develop trust’, and they shared some lessons with us:

- Be ‘very open’

- Invite people in

- Don’t focus on outputs, people are more ‘receptive’ when they can engage in the process and the work becomes ‘a collective priority’

But they do not only bring their skills for building relationships and collaborations.Their tools and processes allow them to gain a holistic understanding of how different elements interconnect.

“Service design has the amazing capacity to coordinate all the layers in a service: the [user] experience, staff workflows, safety, modelling of data, technology…”

Creative Engagement

[In public and third sector contexts,] there is a real flip between logical, evidence-based, robust thinking and analysis’ on the one hand, and the ‘desire for this creative spark’ on the other. And normally, that creative spark falls under the service designer.

At the core of these contributions and where many practitioners see ‘the difference that service design makes if it’s done well [is that] it engages people creatively.’ An interviewee contrasted their work with ‘Town Hall consultations, where you just sit or look at boards [because] they don’t want you to think; they are just ticking the boxes. Service design takes us way beyond that’.

By ‘re-centering everything around the user’, practitioners help organisations ‘understand the needs and aspirations of the people they serve’. A core part of this work is ‘figuring out different ways of engaging [people] creatively’. The openness and creative engagement generated by service design ‘will mean stronger engagement’. The fact that designers take the time to do a great amount of user research and try to design things that work for’ people, not only ‘surprises’ some people but can get them ‘quite enthusiastic’. Practitioners argue that the involvement of users, clients, and other stakeholders fosters empathy, ownership, and passion.

Some participants see design ‘as a means to fundamentally shift democracy’. Its ‘contribution to the civic sphere is that it engages people’ in shaping the world around them, offering ‘a practical approach to participative democracy’.

Organisational barriers

All illustrations for this part were made by Vinishree Verma

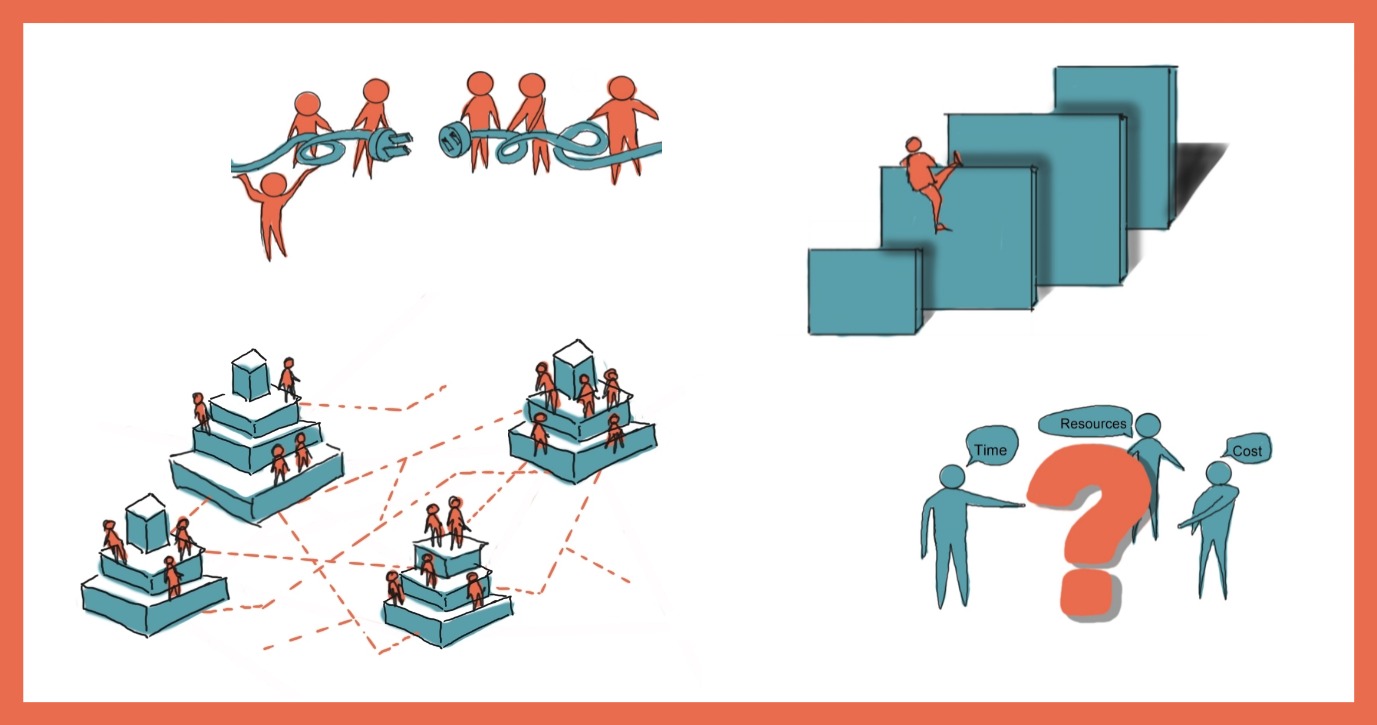

In the previous part, we talked about how service design can help to build empathy in an organisation, to enable collaboration and how it makes a difference in the ways of engaging with people. So, what stops organisations from implementing service design practices?

Barrier #1 time and resources

The practitioners described (service) design as expensive because of the time, resources, and costs associated with:

- bringing designers in as contractors

- implementing the appropriate (system) changes

- up-skilling to be able to deploy service design in an organisation

“The time and cost of learning a new skill, people might need [to] up-skill to deploy service design. […] When you ask people to do things like discovery and testing, if they have never done things like that before, I think the resource against that feels too overwhelming.”

Practitioners told us how difficult it is for people to actually find the time to upskill, embrace new practices or changes as you need to do in addition to your day-to-day job.

“Time is a huge thing in that people might want to be involved but don’t have the time and you just have to work with what you can.”

Some practitioners think that public and third sectors don‘t invest enough which leads to a lack of resources. Service design requires organisational change, which requires money and resources. Not every organisation is yet willing or able to make this investment.

Barrier #2 current ways of working

The way organisations currently work, their hierarchical structures, how decisions are made, their approaches and mindsets are a key barrier for most service design practitioners. They talked about the complexities of working in these environments due to their size and hierarchical organisation, where only incremental innovation is achieved.

“Sometimes in Scotland it just feels like those conversations are just conversations for years.”

The current mindset in the public and third sector is described as being ‘solution-driven, slow and reactive’. Practitioners listed the following things in the current ways of working that are at odds with the service design practice:

- talking instead of doing

- taking too long to act on insights

- resignation and accepting things as they are instead of trying to change them

- not admitting mistakes

- not trusting citizens and communities and holding a more paternalistic view of public services

- wanting to build things before having a shared vision, and thinking that they don’t need to talk to people

“There’s all these sorts of reputational risks, because quite often the things that people have been asked to do are solution-orientated, not problem-solving.”

Some participants also noted how policy is the first step in designing services, and the challenges of designing around the goals set by policy and how these continuously change. The people we talked to noted that designers are often not in positions of power where they can actually influence things, and feel they lack the support they need from leadership positions.

Barrier #3 lack of coordination and collaboration

Practitioners miss design leadership in the public and third sector. They experience a lack of coordination and collaboration which hinders their work.

“Because there is no one there, like above us, able to steer the decision making. It just becomes a little bit like a bonfire. The coordination is what is lacking in a lot of these projects.” Coordination is described as a challenge in particular when it comes to aligning different opinions, interests and approaches.

“Sometimes I think we have too many people in the way. It‘s like too many cooks, too many different opinions and no alignment in them.”

The siloed nature of the public and third sector mentioned by many of our participants also hinders the impact service design can make. People told us how often different departments within one organisation do the same thing but don‘t talk to each other. Many practitioners feel isolated within their organisations as a result of a lack of collaboration. Some practitioners talked about “a big conflict between the public and third sector” balancing different responsibilities and interests which leads to “two big sectors not supporting each other”.

How to overcome these barriers?

Time, resources, current ways of working and a lack of coordination and collaboration are the key barriers experienced by service design practitioners in Scotland. So, as some practitioners questioned, is service design too utopian?

Practitioners shared the following tips with us on how to overcome these barriers:

- getting management as your ally

- being proactive, not just waiting to be asked to do work

- doing workshops with different departments to spread knowledge

The Future of service design

We asked service design practitioners about what they envision to be the future of service design. This is what they‘ve told us.

All illustrations for this part were made by Vinishree Verma

A service designer in every organisation

Practitioners would like to see a service designer embedded in every organisation, and moreover in leadership positions.

“I want to see more people in design leadership positions. I want to see more women in design leadership positions. The side projects I choose to do in my spare time, are helping to build up that community of people to be the potential future design leaders.”

It would be also fascinating to see service designers exploring new spaces in future. Some of our interviewees wished for people to feel brave enough to invite themselves into those places — where they were not previously included — and to start seeing themselves as problem-solvers where they are needed. One of the interviewees urged service designers to explore more ‘fluid spaces‘ like activism, where skills like facilitation, storytelling or problem-solving would be a good fit.

Sitting in between systems and sectors

Practitioners would like to see themselves sitting between systems and sectors that are less siloed. They want to encourage people to do design work that actively joins up different sectors like health care, social care, housing, or transport so that these systems are actually designed together.

Co-design as the default approach

Co-design, co-production and collaboration should become the default approach in future. Develop a culture where service design is ingrained as a way of doing things and not seen as something special.

“Co-designing and bringing people in at day one — just having that as our default working pattern would be good.”

Collaboration across organisations

Some practitioners want to see collaboration as a new target operating model for public sector organisations. For instance, rather than working separately, common issues could be dealt with collaboratively amongst different organisations.

Instead of asking “what is the public experience of X organisation in Scotland during lockdown” we could be asking “What is the public experience of public services during lockdown“.

Practitioners also see a future where the private and public sector are better aligned and working more cohesively, while complimenting each other’s needs and places where some of the services overlap.

“Public sector is not always the right place and doesn’t have the resources to deliver on a lot of the service needs of citizens; the private sector doesn’t always have the perspective and the right driver in order to deliver for citizens’ needs. So there needs to be much more integration between the two [public / private].”

Aspirations for third & public sectors

There are various ways of integrating service design within the public & third sector organisations, and to achieve that the practitioners aspire for changes in the existing system:

- designing a service from start to finish without encountering organisational pressure or constraints

- having a variety in practice, especially in the public sector where one could get bored, frustrated, angry or just needing a break from what they are doing

- having secondment opportunities that may benefit the individual, as well as contribute towards retention and adding further value to the organisation

- building capacity in terms of the right skills and retaining them, particularly in the third sector

- embedding a positive intent to make it easier for the collaborative work between the internal team and short term contract roles

- embedding agile working in local authorities, ‘for consistency across the system that will help to break silos’

Future of service design in Scotland

When practitioners dream of the future of Service Design in Scotland, they think of community empowerment and regeneration. There are a lot of places in Scotland where towns were built around the industry and with time the industry left or became redundant. These places were not designed for the people who actually live there now. Some participants emphasised on regeneration through community participation and collaboration.

Practitioners describe the future as local and community-led and they encourage embedding service design at the micro-level, starting with small community organisations.

“We need to think about it in terms of education and healthcare within the community. We have to think about the big problems that face Scotland in terms of homelessness, the drugs crisis — How those communities directly affected can design solutions to those problems.”

One of the interviewees pointed out the potential of improving healthcare in Scotland compared to the other countries like the USA where healthcare is more siloed. There is a massive opportunity in finding the patterns across the framework that can be adjusted and adopted to the common needs of healthcare in Scotland.

“Things like booking an appointment happen over and over again, every single day in so many different places. So if we actually set out and sort out how that works for patients, for staff, for the system — so that all three get a good deal out of this and we back that up with the software we design, the data we need for it all.”

Expectations from the future Service Design community

Keeping our feet on the ground

Some designers felt that at times there are tendencies in the service design circles to talk about grand ideas. They‘ve highlighted that there is definitely a space for that, but they also need to keep their feet on the ground and make sure that what they are doing is practical and is actually improving things for people.

Engagement and political buy-in

In the future, some practitioners would like to see the service design community getting to that higher level of maturity that attracts more engagement and political buy-in.

Designers skills

Some practitioners said that the future fleet of service designers should be quite comfortable drawing and sharing stuff early, work iteratively and build ideas over time as they test them. They need to understand how to work in an agile environment, ‘because it is so rare to work on a design project that isn’t also digital‘. The future designers need to develop a methodology in which the technical and design systems work hand in hand.

An optimistic take on Covid-19

Some practitioners spoke about creating an optimistic vision of how the response to Covid times could positively impact our work and lives. They hoped for building the service design future by:

- feeding people’s desire for change

- opening our eyes to new ways of communicating and sharing

- softening people minds to experimentation

- eliminating geographical barriers in services

- thinking how everyday‘s businesses could move outdoors

Some felt that the Covid-19 crisis has demonstrated different ways of addressing a situation. Service designers need to hang on to the learnings, so that we don’t forget and revert back to old ways:

“At the moment, we’re all thinking about how to do things in different ways because we have to. Well, let’s not forget that, let’s capture it to keep reminding us. Because again, it’s that thing about power. Because those in power want us to forget those things, right? So we have to make sure that we don’t.”

There was also a call for caution, to not allow the covid crisis to eclipse the climate crisis and focus on creating sustainable economies beyond borders and boundaries.

Awareness and communication of service design

All illustrations for this part were made by Angela

Practitioners talked with us about a lack of awareness, gaps on how to implement it and the risk of oversimplifying the practice. Communicating service design, its approach and value to manage the expectations that come with it, turned out to be both a necessity to grow maturity as well as a blocker to implement service design.

Key gaps in the understanding of implementing service design that practitioners shared with us are:

- people don‘t know what service designers do when they come into a team

- especially across senior stakeholders there is a lack of understanding of what service design is and what value it brings

- there is a lack of awareness of the differences between traditional research (e.g. consultations) and user research

- service design as a practice isn‘t respected as other practices e.g. engineering

- traditional and bureaucratic organisations are not used to the new ways of working offered by service design

- people expecting some kind of magic happening with service design and not understanding the work it actually takes

- service design being involved too late into the process or project

Service design practitioners think that these gaps result into two things:

- oversimplification of service design

- wrong expectations towards design and designers

Oversimplification of service design

Practitioners shared their experience of organisations “just wanting this thing” without really understanding what service design is about. They talked about the risk of reducing service design to its methods and tools.

“I think we become overly simplified […] it‘s almost being over-produced as a thing. It‘s taking us away from the point of being interested in service design to […] a kind of fun workshop activity.”

Practitioner said that people can get obsessed about the process, missing the concept of service design and how it‘s actually delivered. They mentioned the Double Diamond as a useful mental model, however, they also highlighted the risk that it might create a wrong perception of how the work looks like. It might not be “a nice and tidy diagram when you‘re actually applying it”.

Wrong expectations of design and designers

Some practitioners expressed a fear of service design becoming professionalised. A lot of people talk about service design, and practitioners appreciate that service design language is applied more widely. However, they fear that this also might come with a trend of more and more inexperienced people delivering service design activities.

“I think I‘ve seen it go from zero to everyone can do it, and I think we need to find a balance.”

This trend is supported by training that is too simple and not oriented on day-to-day practice, as some practitioners highlighted.

Practitioners also talked about the commercial side of service design and how the practice sometimes even might be misused for that.

“Service design has been commodified depending on how it‘s been bought, who is wanting it, and what they‘re wanting it for.”

How we talk about service design

An important factor that impacts this is the way we talk about service design. Practitioners raised that there is a lot of confusion around what service design is and what it is not. People are struggling with easily defining and communicating service design, which then ends up to become a blocker in doing the work. Some practitioners also highlighted that there isn‘t a consistent approach for user-centred design across the Scottish public and third sector.

“I think all these user-centred design practices are greater than the sum of their parts; there is a gap in how to interact and work together.”

When it comes to communicating service design, practitioners listed the following blockers:

- difficult service design language and jargon

- service design loving to describe itself

- the need for being different

- service design work often being intangible and difficult to show

- service design pushing too hard

“Language is one of the biggest barriers to involving people, and we need to be more conscious, self-conscious of the language we use.”

How can we change the perception of design?

Here are some of the ideas that practitioners shared with us:

- raising people‘s awareness around the value of (service) design

- focusing on building a platform and network

- recognising service design as a ‘specialist skill’

- collecting data on the impact service design makes to projects

- making the process of involving users easier

- having a clear mandate from Scottish Government on how to approach design of services