Quick access

- The people designers work with

- Diverse experiences of engagement

- Getting the organisation on board

- Recruiting and involving users

- To learn more about Co-design

“Do you manage to design not only for but with people? If yes, tell us about it and any new things you have learnt from doing so. If not, is it something you would like to do and what is preventing you from doing it”. Between June and August 2020, we interviewed 15 practitioners and asked them this question. Are you designing with people?

All illustrations on this page were made by Vinishree Verma

They told us about who they work with, the diversity of their experience and their aspirations. They also described the challenges and some strategies when trying to design with people.

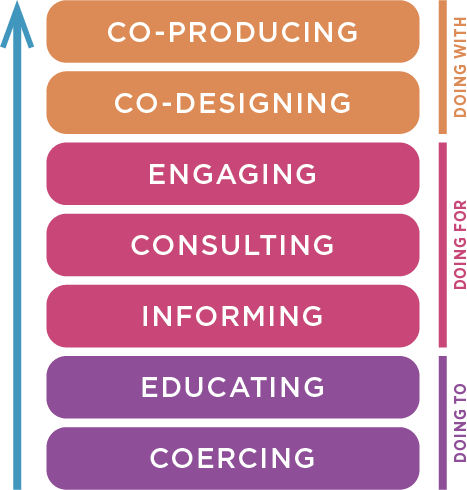

Participation ladder. Source: Iriss.org.uk

The Scottish Approach to Service Design (SAtSD) provides a framework on how we design user-centred public services putting a particular focus on working with people and involving them in the design and delivery of the service. The practitioners we talked to were all aiming to do it with various levels of success.

“The vision for the Scottish Approach to Service Design is that the people of Scotland are supported and empowered to actively participate in the definition, design and delivery of their public services (from policy making to live service improvement).” — gov.scot resource

The people designers work with

When we asked practitioners who they work with, they distinguished three categories of people:

- the design team

- clients & stakeholders

- users/citizens

Some highlighted the benefit of having a user researcher in the team as they often tend to be closer to the users. They ‘help tell the story’.

Some interviewees who were consultants or contractors mentioned that sometimes they worked closely with the clients as a team where they were either the research participants or the expert educating the practitioners. In some cases, they design and plan together but on other occasions they could be much more removed from the work.

Some also expressed an increased difficulty in engaging with people depending on the participants they work with. Internal users were perceived to be easier to engage with compared to citizens. Vulnerable users were described as the most complex to engage with.

While practitioners agreed that involving people is core to service design approaches, they also acknowledged that not all service design work is human-centred and highlighted more commercial applications of service design.

Our research shows that as a community, we aspire to embed meaningful participation and involve citizens and users as part of the design team. However, we are not quite there yet and we are still learning how to do it:

“There’s a lot in there around citizen participation and upscaling. […] there is a lot more that we should and could be doing to bring citizens properly into the process of co-design. […] we need to figure out how to do that. What’s practical, what’s safe. What is the right way to go about that. What’s the effective thing to do.”

Although users and stakeholders’ involvement is seen as critical to the design process, practitioners highlight that it needs to be appropriate and tailored to the project:

“[designing services for people in high risk of suicide], we couldn’t work with them. We had to work with professionals and practitioners to get their stories”

Diverse experiences of engagement

Some felt they could only manage minimum engagement. While others felt like the practice might look like it’s user-centered and participatory but often isn’t really:

“It’s quite easy to confuse involving people in your process, with designing with them. You can involve people in a design process from a user research point of view, and it becomes about them answering questions that you have already thought about, or them interacting with prototypes […] Whereas [in] participatory design you might not know yet the questions that you want to ask, you just know that these stakeholders need to be together in a room so that we can frame the problem.”

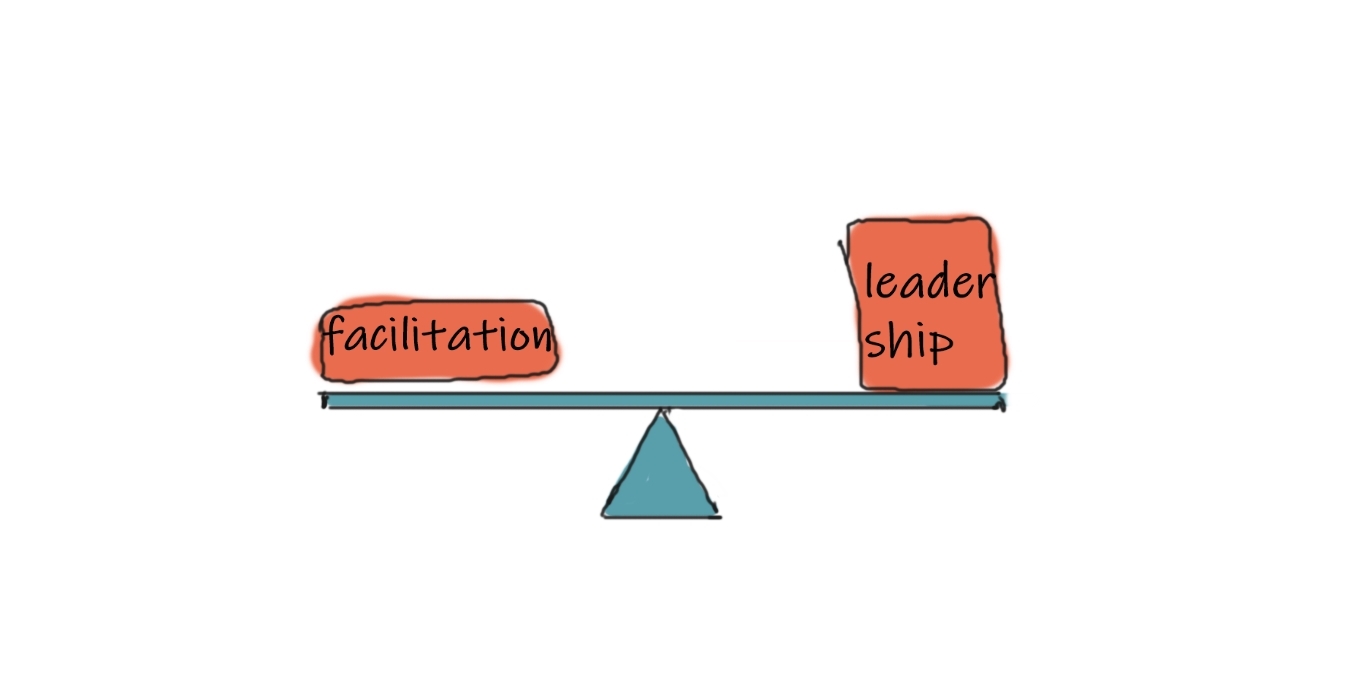

The right balance between facilitation and leadership

It’s also about finding the right balance between facilitation and leadership to involve the people on the right level:

“[A project] involved everyone in the community to design this website for themselves, and it was so unusable, cause they just threw everything at it. They’ve just gone for ‘everyone can post and designing wireframes’, and it was really nice, it felt nice, but what the designer should have done was take the insights of what was being inferred and turn it into to an actual working design based on their expertise as a practitioner, because they know what works.”

Getting the organisation on board

Before even involving the users, you might have to make sure you have the stakeholders’ buy-in and it’s not easy.

The organisation is not ready

The organisation might not be mature enough to work this way, and it might put people off. Some practitioners experienced negative responses from teams about (service) design which they explained by a fear of change and resistance in doing things differently.

“When you start hearing the truth from people or something you didn’t expect, it can be really jarring and unwelcome. So if teams have had an experience like that of service design, they might be apprehensive to continue or to do it again.”

“Fear from front-line and mid-management staff […] I try and do the kind of communication and co-design cycles with the staff, the teams. But I definitely found that individuals can be a real barrier there because they are scared of change, they’ve seen it before, it failed last time. Organisational memory is really strong. Often people in local authorities have been in the same job and will never leave in their whole life”

Being honest and ok with experimenting

Some practitioners were honest about being unsure and presented the process as an experiment:

“We tried a few things out, we experimented. […] We said to the participants: we’ve never done this before, we don’t know if this is going to work, tell us if it doesn’t, we’ll see if we can change it on the fly and we will see what we learn. People were open to that because we were honest and they were very helpful and supportive in terms of how we managed to deliver the research and conduct the activities.”

Building design capacity in the organisation

One practitioner shared this experience in their organisation:

“We’ve sent […] different managers on a service design training […] the fact that everyone knows the language now and everyone knows why we are doing things, why service design or design thinking as an approach is going to be beneficial in the long run, I think it’s a really good starting point. Sending managers on the training was really helpful”

Recruiting and involving users

Challenges

Practitioners said that remains an issue with the ‘willing’ user being over-researched:

“ We‘re seeing it over and over again, […] we get a lot more female participants, we get more international [users] than Scottish [users], and we‘re not entirely sure what the reasons for that are.”

Some felt that we have gaps with some people we never reach. Making sure we engage safely with people without re-traumatising them is not easy either.

Accessibility is still mentioned as a big challenge. The ways we research and design using sticky notes for example do not work for everyone. Some also mentioned the fact that our methods are ‘quite extractive of people’s experiences, of their time and energy’.

Some strategies and their limitations

Having a regular user group was mentioned as a strategy to get a fresh set of eyes to see different things but when users become part of the team they can become biased:

“[Having a regular user group] is not a brilliant way of doing things. […] By the second or third meeting they [the team] could see that [the users] had been so skewed by our own thinking, by previous activities. They were almost already members of the team and some of them actually became members of the team.”

The importance of creating the connections to have the right relationships was highlighted:

“I partner up with people who have that outside relationship and use their skill sets to work with citizens. Which is great and quite a different thing for me. […] I‘m sort of partnered with a brilliant talented person, who is able to take on board all of the responsibility of working well with citizens.”

“We just had to be really thoughtful about that process. The way we get around it is we partner with a lot of people […] with organisations who already have these close relationships with people.”

Another strategy was to grow users’ skills:

Some practitioners explained that while designing with people they started to train them on conducting interviews, did some coaching, and some even recruited them as interns.

“We run this programme to teach young people how to research and publish their own newspaper […]. Instead of doing extractive research, you were empowering them to go and do their own research, and turn it into a newspaper. So […] we taught them how to do stakeholder mapping, interviewing their friends, and so all round it was a really kind of collaborative value model, because young people got skills and employability skills, and something to show. […] That is a less extractive model that involves people. It’s much more about co-development.”

To learn more about Co-design

From user-centred design to co-design — blog post from GOV.UK

Beyond sticky notes and the Co design quick test by KA McKercher with their 4 questions:

- Is there mutual learning (the -co’ bit)?

- Is there something being made? The ‘design’ bit?

- Is there a degree of co-deciding?

- Are people with lived experience recognised for their time?